Leaving Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam we hopped on a bus and made the relatively short trip over to Cambodia, ultimately settling in Phnom Penh. Like many of the previous countries in Asia we’ve been in, this was my first time there, but Kirk visited Cambodia 12 years ago on his way back from the Peace Corps. Prior to leaving the States back in December, Kirk shared with me about what he had learned during his previous visit to Cambodia. Shocked by what I was hearing, it took no convincing to add Phnom Penh to our list of places to go. If you are as unaware as I was, Phnom Penh is the capitol of Cambodia and home to the most known “killings fields” and prison from their last civil war.

If you’ve been following along and were surprised by some of the history I shared about Vietnam, keep reading, because somehow the events that have occurred in Cambodia also slipped through the pages of my school history books. I’d heard of the killing fields before coming to Cambodia and even watched a few movies about what happened, but nothing impacts you like learning history behind the history, visiting the location of mass genocide, and meeting the peoples who lived through such an atrocity.

First, a little back history to get us all on the same page. It gets a little complicated, but try to hang in with me! I’ve learned from this trip that it’s only through a larger view of history that we can see how things came to be rather than simply what is or was. Although, if you’d rather just read about the genocide, instead of how the genocide came to be, skip down to the line that starts “That’s the back history.” Otherwise, we’ll start around WWII.

Like Vietnam, when the start of WWII came around, Cambodia was under French rule. During WWII, the Japanese came into Cambodia and ran the French out, but after WWII the French wanted to again have control over Cambodia. Unlike Vietnam, in 1946, France and Cambodia ended up coming to a compromise in which the newly appointed Cambodian King Sihanouk maintained rule, but France held some oversight in the country while also providing military protection. However, after a few years, Cambodia decided that they didn’t want to be under French rule at all. King Sihanouk worked to renegotiate terms, and since the French were already battling Vietnamese rebels in Vietnam by this point, in 1953, the Cambodians were fully given power of their country as the French gave up their hold to avoid opening a second war front.

With independence and democracy came the creation of several political parties. Notable among these groups were “Sangkum,” the people’s socialist party of which Sihanouk was apart; the Khmer Rouge, a communist group led by a man named Pol Pot; and what was eventually named the Social Republican Party, a more conservative, anti communist group led by Nol Lon. By the late 60’s the conservative group had grown immensely and in 1966, Nol Lon was elected Prime Minister and worked right under his socialist counterpart who was still Head of State, Sihanouk.

While all this change and inevitable political tension was happening in Cambodia, Cambodia’s neighbor, Vietnam, was engaged in a civil war between the North and South (in case your timeline is confused, this was the Vietnam War that the U.S. ended up taking part in). Cambodia was considered “neutral” in the Vietnam war at this time, but while saying they were neutral, the head of state, Sihanouk, left the borders open, ultimately allowing the North Vietnamese (communists) to funnel weapons and troops through their country into South Vietnam. While Sihanouk was allowing this, there were many anti-communism Cambodians who wanted the borders to be closed, including Nol Lon, the newly elected Cambodian Prime Minister.

This led to a coup. In 1970, when Sihanouk, Cambodia’s Head of State, was out of the country, a group of anti communists led by a U.S. supported Prime Minister Nol Lon, overthrew the capital of Cambodia and shut down the borders. Nol Lon then also appointed himself president over Cambodia.

In the midst of everything happening in the last three paragraphs, sometime in the 60’s news made it to the U.S. about the North Vietnamese trail of weapons and soldiers being snuck into South Vietnam via Cambodia/Laos. In 1965, prior to Nol Lon overthrowing the government, the U.S. began to carry out “secret” bombings all over east Cambodia in attempts to destroy the trail. Over a period of eight years, the U.S. dropped over 2.7 million tons of bombs on Cambodia (more than the entirety of bombs used by the allies in WWII). Hundreds of thousands of Cambodian civilians died and those who survived were left with no home to return to.

But that’s not all that was going on in this time period – in the midst of everything happening in the last four paragraphs, the earlier mentioned communist political party led by Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge, slowly began a series of attacks on the Cambodian government in 1967. As the U.S. continued to show support for Nol Lon (who, as a reminder for you, was president of Cambodia by 1970) the U.S. was also continuing to carpet bomb the eastern half of Cambodia. The communist party in Cambodia saw this contradiction of the U.S. supporting the man in power while bombing his people as a way to win the Cambodian people over to their side. The Khmer Rouge presented themselves as a peaceful party and used the hurt, anger, and fear felt by villagers from the bombings as a way to convince people to turn away from both the U.S. and their own government, turning them towards the Khmer Rouge – towards communism – or at least a skewed view of it.

That’s the back history. What follows is the genocide.

From 1970-1975 Cambodia found itself in a civil war – the Khmer Rouge party against the U.S. backed Cambodian Government. The U.S. “pulled out” of Cambodia in 1973 (though most of our support had been done quietly and with very few troops to begin with) and two years later, the Khmer Rouge won. On April 17th, 1975 the Khmer Rouge rolled into the capital and declared this a new beginning for Cambodia. They named April 17th, 1975 the start of a new calendar, year 0, for their people. Many people cheered, welcoming the soldiers, thankful that the killing and war must be coming to an end. Unfortunately, this was only the beginning of the terror to come.

Within days of entering the capital city, the Khmer Rouge announced an immediate evacuation of the whole city. Some inhabitants were told to leave the city for three days while the Khmer Rouge prepared the city for its new life. Others were told to leave because the U.S. was about to bomb the area. In the end, it was all lies, but anyone who refused to leave was shot on the spot.

Though Phnom Penh was once a city of around 600,000 people, the U.S. bombings in east Cambodia from the years before had forced many villagers to move to the city and by 1975, it had a booming population of well over 2 million. In less than a week’s time, the 2 million inhabitants of Phnom Penh walked away from everything they had and headed to the countryside. By the time Pol Pot himself entered the city on April 23th, the entire place was empty – even the hospitals.

The Khmer Rouge believed in a very extreme version of something called Maoist Communism. While believing that society should be classless, they also elevated the status of peasant and farmer above everything else. They believed that “new people,” or educated society, were the problem in the world and that their country needed to restart at a very basic level of “old people” or, basically, peasants and farmers to be pure. The Khmer Rouge closed their borders and convinced the international community that they were helping their country recover from corrupt capitalism, and for the most part, the rest of the world believed them.

All the while, inside Cambodia, as they gradually emptied out all the cities in the country, new villages and labor camps were set up. Many “city people” were forced into labor camps where a lack of food, abuse, and harsh conditions persisted.

The Khmer Rouge prohibited all formal schooling and started up “education” programs of their own where they taught things like, “there are no diplomas, only diplomas one can visualize. If you wish to get a Baccalaureate, you have to get it at dams or canals” (quoted from a museum we went to). Children were taken from their families, made to labor long hours in the fields, and many were forced to join the troops. Troops of child soldiers were trained up and taught allegiance to the Khmer Rouge over everything, including family. Former schools were turned into prisons and warehouses. Children were considered “pure” and were used as “detectors.” They would often have children go into a village and point out “traitors” (people who had actually done nothing wrong) who were then executed.

Anyone who had worked for or supported the previous government was a traitor. Anyone who was educated was considered a threat. Intellectuals, the rich, the religious – all targets of this new regime. Many “traitors” were killed on the spot, thousands of others were imprisoned, tortured, and executed.

The Khmer Rouge openly taught that they believed it was better to kill an innocent than to have a traitor among you (Their leader, Pol Pot is quoted to say, “Better to kill and innocent by mistake than to spare an enemy by mistake”), so any suspicion of broken allegiance or questioning of the Khmer Rouge merited death. Though former government workers and educated “new people” (doctors, teachers, nurses) were targeted first, eventually, as paranoia grew, so did the death toll. By the end, no one was safe from accusation, even high ranking members in the Khmer Rouge.

Between 1975 and 1979 (y’all, this was not the long ago), the Khmer Rouge managed to essentially “secretly” kill somewhere around 1.7 million people (some estimates are as high as 3 million, the actual number is still unknown) – somewhere around a fourth of Cambodia’s population (let that sink in, approximately 1 in 4 people living in Cambodia died under the Khmer Rouge). I say secretly, because most of it was hidden from the world. People escaping from Cambodia tried to tell what was happening, but many in the international community had been led astray by the Khmer Rouge to the point that the accusations fell on deaf ears.

In 1979, the killing only stopped because, while tormenting their own people, the Khmer Rouge also had a battlefront going on with the Vietnamese. The Khmer Rouge were in a land battle with the Vietnamese and launched and attack against them in 1977. The Vietnamese counter attacked in 1978 and after eventually deciding that they definitely did not want the Khmer Rouge in power, in 1979, the Vietnamese occupied the Cambodian capital. The Khmer Rouge retreated West, and continued living in the Thai border region as they still occasionally engaged in guerrilla warfare.

The international community, still largely unaware of what had actually been happening in Cambodia, wasn’t willing to recognize the Vietnamese control in Cambodia, and appointed a member of the Khmer Rouge to the UN to represent the nation (Yes, not understanding the magnitude of what had happened, the UN appointed a member of the party responsible for millions of deaths as a representative for the country, after the Khmer Rouge was no longer in power).

Within Cambodia itself, the Vietnamese placed a man by the name of Hun Sen in power. Hun Sen was a former Khmer Rouge battalion commander who had fled to Vietnam two years prior to the Vietnamese take over. He fought with the Vietnamese to take back Cambodia.

Gradually and eventually, the world began to realize and accept the truth of what had happened, but to this day, justice has never fully been served. Unbelievably, Pol Pot, the leader of the Khmer Rouge, who is responsible for the death of 2 million people, never went to jail. When he and his men fled to the west, he just kept living his life, still controlling the loyal Khmer Rouge members. Eventually, his group had a conflict, and in 1997, after he had his right hand man assassinated, some of his own members threatened to turn him over to the US. Not long after the threat, in 1998, he was found dead. His wife said it was a heart attack and had him cremated before his body was examined, but the accepted theory is that it was actually suicide by poison.

1999 is considered the official end of the Khmer Rouge.

In 1997, Cambodia asked the UN to help create a court to carry out cases against the leaders of the Khmer Rouge. In 2007, the court became operational. In 2010, a lower ranking member of the Khmer Rouge was convicted and sentenced 19 years in prison. In 2014, two higher ranking officers were convicted and sentenced life in prison.

That’s it. Three elderly people (one of which is now 91) are in jail for a Genocide, and it took 30 years for them to get there.

(As a side note, the man who was convicted in 2010, called “Duch,” has a fascinating story himself. In the Khmer Rouge he oversaw the deaths of around 20,000 people, afterwards eventually become a Christian, and, under a fake name, was working closely with World Vision when he was found out. He went willingly with authorities and plead guilty at the trial, confessing everything he’d done)

What’s even crazier than the lack of convictions is that the man the Vietnamese put in power, Hun Sen, who was once apart of the Khmer Rouge – is still in power. If you heard the news a couple of weeks ago that the US has recently sanctioned Cambodia (this announcement actually came the day before we were leaving Cambodia, and we were glad to be getting out 😬) – it’s because of this man. Though mass genocide is no longer on his list, he is still known to kill people who oppose him and he recently eliminated the only other opposition party in the country. If you speak out against him or question what he’s done, they will arrest you.

Anyway, if you hung in there through that long explanation, way to go! I found myself shocked all over again as I wrote it. There is so much we don’t hear about at home and it’s crazy because even we when we do hear about it – it’s on the other side of the world, so it tends to not hit us as hard. But when you find yourself sitting in a taxi with a man who tells you that he is lucky his father was a farmer, and look around and realize that you see very few grey haired individuals walking the streets around you, you begin to realize just what was lost and how many people were affected.

As far as what we actually saw and did in Phnom Penh – the first place we visited was Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum is a former high school that was turned into the most secret of the 196 prison/execution sites of the Khmer Rouge after the schools were shut down. It was also known as S-21, and somewhere between 17,000 and 20,000 individuals passed through this prison, of which there are only seven known survivors (though the estimated number of survivors is around 200).

When an individual was brought to Tuol Sleng, it was because they had been accused of something. Often the prisoner didn’t know what they had been accused of as it was all fictitious, but they were expected to confess. Upon arrival, their picture was taken and they were interrogated. If the Khmer Rouge couldn’t find anything in the interrogation to link them to a crime, they would torture it out of the person. It is said that the only doctors available at the prison were there to keep people alive for more torture. A person was tortured until the Khmer Rouge had a documented confession for which the person could be executed – or until they named other traitors – after which they were still executed. Based on what we learned in Cambodia, Wikipedia has a pretty accurate description of what torture and everyday life looked like at the prison if you want to know more – it’s horrifying. Below are pictures of what we saw.

A view from the top story of one of the buildings. The building seen here was used to torture and house prisoners. The stand with pots underneath was once used to hang ropes that the high schoolers climbed during PE courses. Once the school became a prison, the pots were placed underneath to torture individuals, dipping their heads in water as they hung from above. To the right you can see one of the 14 white graves on the property. These caskets house the corpses of the last 14 victims of this prison. Their bodies were discovered by the opposing troops after the Khmer Rouge fled.

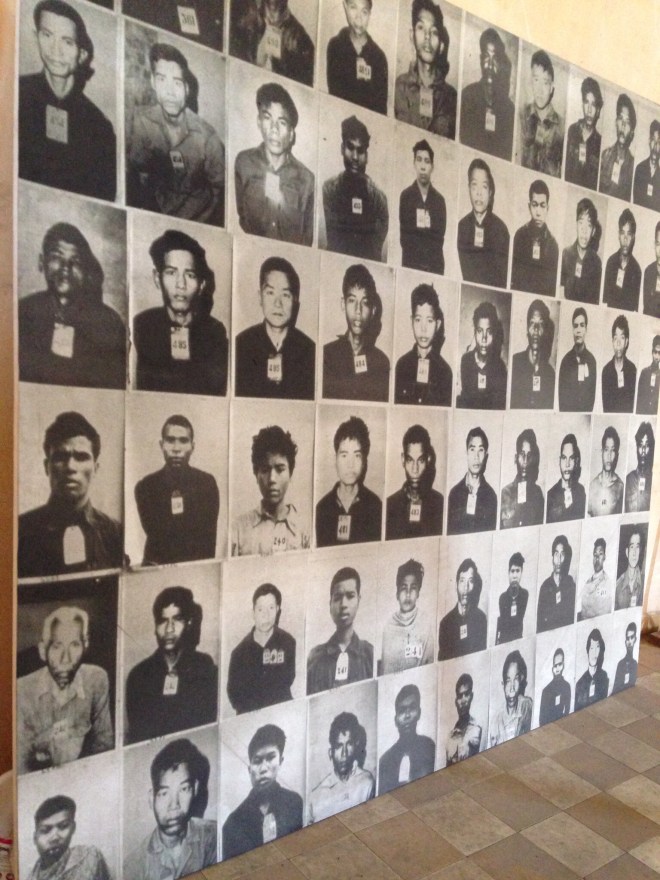

I mentioned the the Khmer Rouge took pictures of all their prisoners as they entered the prison. The walls of this now museum are lined with the faces of those who lost their lives at the hands of the keepers of this site.

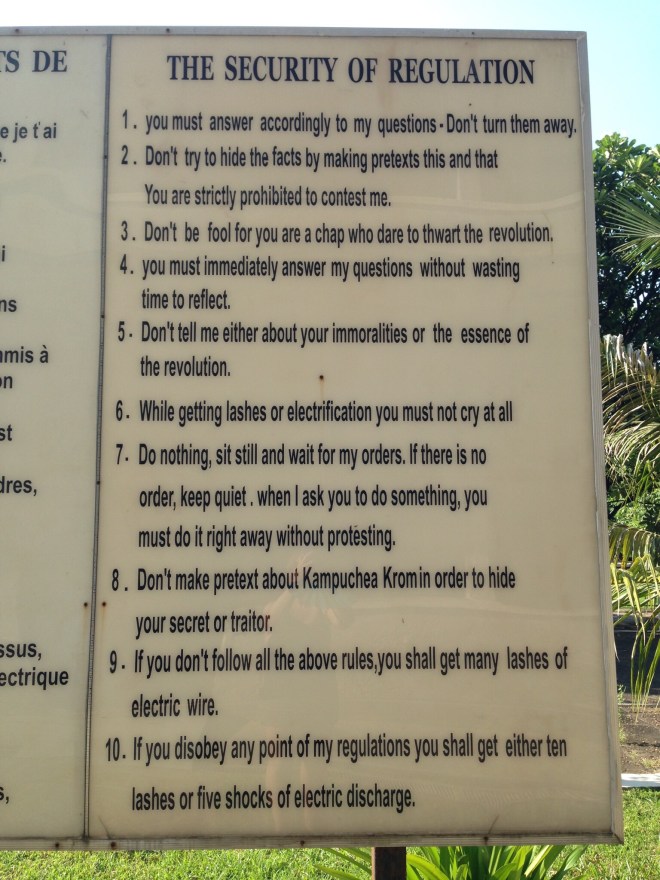

These are the 10 rules prisoners were told when they arrived at the prison.

Multiple classroom turned torture rooms are still set up. The beds that people were shackled to sit in the middle of an empty room with a single gruesome picture of an actual person who was tortured there hanging behind it.

Old classroom chalkboards still hang in many rooms.

One of the buildings is wrapped in barbed wire, that, when prisoners were still housed here, was electrified. This building contained classrooms that had been converted into make shift single cells for prisoners.

Cinderblock single cells

Brick single cells and a view of the sections of classroom walls that were cut out to create doorways between the rooms filled with single cells.

Single cells with doors

A view from behind the barbed wire

This is just a stairway in the old school building. I loved how the light shone through the holes.

The final exhibit we visited at the museum is one that changes pretty often. This time the focus was on the children affected by the Khmer Rouge reign. It talked about how the children became soldiers and worked in the fields – what it was like for them to attend these new “education systems” focused on brainwashing them into the Khmer Rouge mindset. At the end of the exhibit, they had interviews posted of questions they had asked survivors of this time period. One woman was asked, “What is your message to the young generation?” The short of her answer? She wants young people to avoid scapegoating and seek solidarity.

Sometimes enemies only become enemies because we are looking for someone to blame. I couldn’t help but think, that’s probably something that all sides of the aisle in the U.S. need to consider right now.

As we began to walk out of the museum, we passed this guy.

Isn’t he beautiful? I’m not sure why his home is on the museum grounds, but I don’t recall seeing a peacock quite like him before. The yellow on his face was so vibrant!

Isn’t he beautiful? I’m not sure why his home is on the museum grounds, but I don’t recall seeing a peacock quite like him before. The yellow on his face was so vibrant!

I’ll take a brief pause here and show you around the city of Phnom Penh some before going on to the next place we visited, as it was quite heavy too.

Independence monument, celebrating their independence from France.

You can’t see him well, but this is a statue of King Sihanouk, who led Cambodia to independence. Independence monument is in the background.

A better view than the previous blog of some of the crazy power lines we’ve seen all over Asia!

Cambodia Vietnam Friendship Memorial – built in the 1970’s as a thank you to Vietnam for freeing the Cambodian people from the Khmer Rouge.

A statue near the palace – I wanted a picture of the front, but felt weird taking it with the guys laying under it. This day the city was celebrating the King’s birthday and most patches of shade were packed with people!

An entrance to the palace grounds, we didn’t go in because of the cost and crowds, but it looked beautiful from outside the gates!

And now we move to the second eye opening, historical place we visited in Phnom Penh, the Killing Fields.

The term “Killing Fields” actually encompasses more than 20,000 mass graves sites scattered through Cambodia where an estimated 1.3 million of the victims of the Khmer Rouge are buried. Though initially many individuals were killed and carried to the sites, the Khmer Rouge eventually realized that it would be more efficient to have people take themselves to the sites before killing them. They often had people dig their own graves or kill others there before eventually being killed themselves. Because the Khmer Rouge wanted to save bullets, many people were beaten to death with a variety of tools. Their skulls that remain bear witness to what happened.

Right outside Phnom Penh is one of the well known mass grave sites called Choeung Ek where many of the victims of the S-21 prison were killed and buried. Many of the bodies in this area have been exhumed, examined, and are now in a memorial at the site, but 49 of the 129 mass graves remain untouched. As you walk around the gravesites, a few pieces of clothing and bones can be seen emerging from the dirt. The keepers of the site regularly pick up and place unearthed pieces in glass boxes around the site, but the rains inevitably raise up these pieces of the past, remembrances of what happened.

Below are a few pictures from the site.

There are several areas fenced off that mark where the now exhumed bodies once lay. Most of the fence poles are lined with bracelets left by visitors in remembrance of those who died. This grave in particular once held more than 100 women and children, most of whom, unlike the many other graves in the area, were buried naked. The tree next to the grave is where many children were killed. The audio tour we listened to said that babies were held by their feet and banged against the tree until lifeless. It’s so unimaginable that it’s difficult to believe, but it’s not just story – when this site was discovered, brains were found on the tree and former members of the Khmer Rouge have admitted this is what happened. It’s sickening.

Some of the grave sites. Though you can’t tell what we are standing on from the picture, they have built wooden platforms around the graves so that visitors are not walking directly on the sites.

One of the victim clothes, gradually coming unearthed.

The memorial that was built that houses the bones of over 5,000 individuals exhumed from these grounds. Inside, the bones are on display.

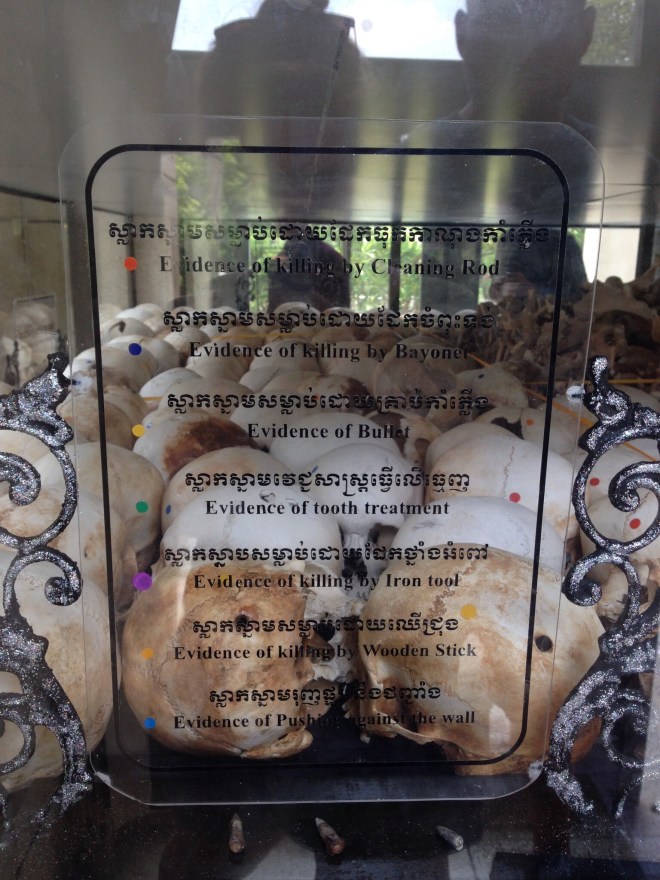

The skulls of the victims are displayed in the bottom layers of the memorial.

The skulls have been examined, sorted by age group, and marked with a sticker indicating how the person was murdered.

Even in death, they attest to what happened. It’s painful to look at the holes in these skulls and consider how they got there.

Even in death, they attest to what happened. It’s painful to look at the holes in these skulls and consider how they got there.

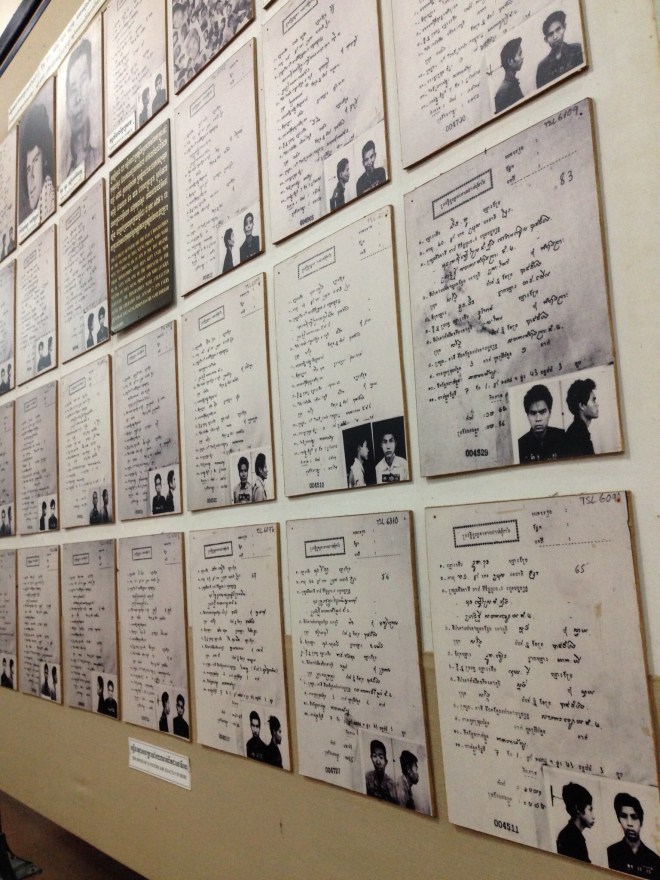

At the very end of our visit we stopped by the small museum they have on site at the killing fields. Housed in cases were examples of the weapons used to kill thousands of people at this site. They also had copies of paperwork of some of the victims from S-21 prison on display. It’s shocking how long it took the world to catch on with so much evidence on hand.

Paperwork from the S-21 prison with victims photos.

In all, reflecting back, perhaps what speaks as loud as the sights we saw is the way in which the information was presented. In Vietnam, most of the museums felt like propaganda – a way for Vietnam to tell the story they wanted to have heard. Cambodia was the opposite. Their museums and historical sites felt like a plea.

“Please look, see, here is the evidence of what happened. This actually happened. Here are the skulls, here are the torture weapons, here are photos, here are mass graves. Here is what scientists found by looking at all these items. Here are the confessions.”

The proof and pleas are undeniable and heartbreaking. It’s shocking how long we stay blind to our neighbors and scary to consider what we may be blind to now. As I mentioned before, even now in Cambodia, the current leader is setting himself up as the sole power. He’s silenced the free media and disbanded other political parties. I fear the terror may not yet be over for the people there.

If anyone is interested in learning more, there are two movies we’ve watched that tell the stories of people who were actually there. A 1984 film entitled “The Killing Fields” tells the true story of two journalists who were in Cambodia when the Khmer Rouge took over Phnom Penh. It was certainly one of the earlier looks into the atrocities and give a different perspective than the other film we watched.

The second movie we watched is a 2017 film called “First They Killed My Father” based on a book of the same title, written by a woman who was a child during the genocide.

This was a long and heavy blog, but I think it’s a story that needs to be told.

The next blog will also be about Cambodia, but will be much lighter and mostly pictures. Our next destination was Siem Reap, home of Angkor Wat 🙂